Questionable Advice

Some things we do are complex. It’s natural to seek advice about “the right way” to do them from those who have gone before, especially when first starting out.

Imagine you know little of carpentry, but have ambitions. You could go to Domicile Depot, buy a bunch of wood and nails, then set about building yourself a house. With decent problem-solving skills, you might be able to throw up a structure able to withstand a stiff breeze. You’d likely be in for some discomfort the first time it rained.

Humans have been building shelters for…oh, let’s say fifty-thousand years. Load-bearing mammoth tusks supporting hide roofs. There’s been a lot of progress on that front in the intervening centuries, and that progress was passed down as knowledge, and much of that knowledge has been recorded. Luckily for you, some of it is almost certainly recorded in a language you can read.

It would be foolish or arrogant—or both—to plow right into a complicated endeavor like home construction without at least trying to partake of that font of knowledge. We’re social creatures who learn from each other. In fact, we’re the acme of the animal kingdom when it comes to learning from each other. No need to reinvent all those metaphorical wheels: just draw upon the best practices of the past.

Picking the best advice is important, of course. Lots of people are sharing their expertise, but some are more expert than others. Some are charging for their advice—nothing necessarily wrong with that—but that poses another question: is it worth the cost? Sometimes free advice from a master is far more valuable than a paid class taught by a poseur.

Being a humble learner, an eager padawan, an honest seeker of truth impassioned to acquire expertise, you look for tutorials, demonstrations, treatises, and blueprints. You find blogs or YouTube videos by those who have gone before you and want to give back. You look closer and closer at the objects of your passion—the instantiations of your chosen craft that you encounter in the world—and you find yourself peering beneath the surface detail as though you were gifted with x-ray vision, picking out the bony scaffolds that give the thing its structure.

I do, at any rate. My big, complex task right now is becoming an author. I want to write fiction that people want to read, stories that people love, novels that inspire and entertain. For decades I’ve been looking intently at stories, narratives, films, and books, wondering what made them tick and what factors made a few of them great and many of them not-so-great. For the last few years, I’ve been drinking in all sorts of writing advice. Most of it being the free kind, in the form of blogs, magazine articles, podcasts, etc.

I’ve had that wide-eyed expression throughout that time: sucking it all in, finding some bits more valuable, more applicable, than other bits, taking it all “under consideration,” so to speak…

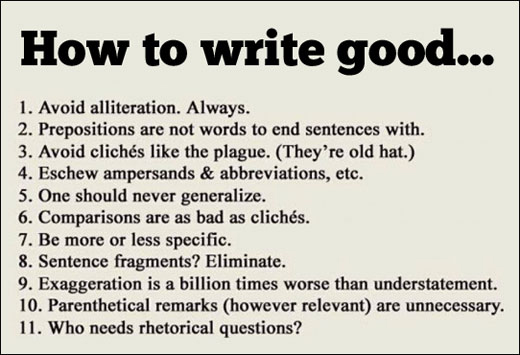

There’s a milestone you reach with regards to advice when you’re practicing your craft. Well, there are many milestones, but there’s this one that just struck me: you get to a point where you can disagree. You reach a stage where, still listening to all the advice you can, you suddenly find you know enough to argue back. You see the short-sightedness in something you’ve been told.

I was reading a writer’s blog of advice on novel revisions. Novels are big things, tend to be terribly complex, and always need lots of revision. And I was following along, point by point, going down the list, thinking: “That first point is good. Yep, and that second point is something I already do. I use the technique this third point is describing without having to think about it. I’m doing the next one as well. Wow, I’m already doing most of the things this person is recommending. In fact, if I were put on the spot and asked to give my own novel-writing-and-revising advice, I’d be echoing much of this advice.”

Then I came to a point I disagreed with. And I knew why. I knew that the advice was generally good, and would have been useful to a novice, perhaps…but it was over-broad. If followed slavishly, the rule would produce a novel without enough stylistic variation. I wouldn’t have had the perspective to see that a year ago. I wouldn’t have had the experience that a couple hundred thousand good words gives me. I wouldn’t have noticed many great writers breaking the very same rule, to good effect.

I think the same thing happens for everyone who tries to do something that takes a great deal of education to get right. There’s a moment when you move from being someone who knows so little that all advice is welcome, to someone who knows enough to be able to debate a point or two. You become someone who can tell that some advice is flawed, and can point it out. It’s kind of a great moment to experience.

Lastly, let me state that, should I live to be 100 and have scores of novels to my name, I’ll know there’s still lots for me to learn about the craft of writing. There’s always more to learn, and always someone new to learn it from. This is post isn’t about not needing to learn anymore, or not needing any more advice—it’s about that cool transition when you become someone who is more of a participant in your craft than an ambitious beginner.

If you're going to use irony, make sure you really mean what you say.